How to Protect Your Intellectual Property in the Highly Competitive – and Highly Essential – Field of Agriculture

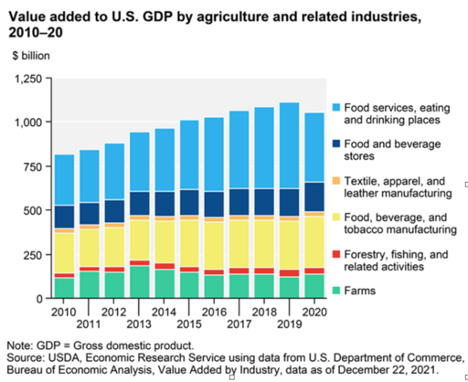

Agriculture, food, and related industries contributed $1.055 trillion to the U.S. gross domestic product (GDP) in 2020, a 5-percent share. In the same year, 9.7 million full- and part-time jobs were related to the agricultural and food sectors—10.3 percent of total U.S. employment.

Feeding a world population of 9.1 billion people in 2050 will require raising overall food production by about 70 percent. This increased production demand faces growing challenges caused by evolving pests, pesticide resistance, and other crop threats brought on by extreme weather. These economic and social factors are driving increased innovation in nearly every area of crop science. And with the growing market and increased innovation, venture capital investors are making record investments in this sector—a record $5 billion was invested in AgTech across 422 VC deals in 2022.

Innovation is taking place across the industry, including:

- New chemicals and biologics for things like pesticides and crop stimulation

- Advances in data science and precision agriculture

- Advances in robotics and other areas of crop automation

- Innovations in seeds and asexually reproduced plants for new and improved traits

As the innovations vary, so do the forms of intellectual property protection available to each. IP protections useful for agricultural innovation can include patents, plant variety protection, trademarks, and trade secret protection. It’s not surprising that some entrepreneurs struggle to choose.

So which form of IP protection would be best for your agricultural innovation? Here, we will review various options that should be a part of your considerations.

Utility Patents

Utility patents—going back to 1790 and enshrined in the U.S. Constitution—are often the go-to for intellectual property protection in the agricultural sector. The diversity of inventions that can be claimed in a utility patent can reflect the richness of technologies in this sector, including equipment, precision agriculture, pesticides, herbicides, fertilizers, genetic engineering, microbes, and plants.

It wasn’t until 1985, however, that case law established the patentable status of plants. Since then, patent laws in many jurisdictions have grown to cover plants and their parts and components. A wide range of claims is often admitted in relation to genetically engineered plants, including genetic constructs and their components, as well as modified cells and plants. Plant-related utility patents may cover DNA sequences, promoters, enhancers, individual exons, plasmids, cloning vectors, expression vectors, nucleic acid probes, amino acid sequences, transit peptides, isolated host cells transformed with expression vectors, and processes to genetically modify plants and to obtain hybrids.

There are a few main categories of utility patents you should be generically familiar with. The first, which you’ve probably heard of if you have ever watched Shark Tank, is the provisional patent application. This is often the first step many entrepreneurs take in the patenting process. It starts the process and helps to minimize the immediate costs.

Know that a provisional patent application is never examined and never turns into a patent. Provisional patent applications also never publish (although they may become publicly available if a non-provisional application is filed). If a provisional application is filed, then a non-provisional application must be filed within twelve months of the first filing date for your provisional application.

A special form of non-provisional application is an application filed under the Patent Cooperation Treaty (PCT). PCT applications are similar to provisional patent applications because they allow you to delay some costs involved in the patenting process, and they will never directly turn into a patent. Unlike the provisional application, PCT applications are examined for patentability and publish 18 months from the earliest priority date.

If you are planning to pursue foreign protection in the PCT signatory countries, the PCT application allows you to delay until 30 months from the earliest priority date before incurring the costs of filing those applications. You also have the benefit of that international examination to guide your filing decisions.

157 countries have signed the PCT, but there are several that have not, including Taiwan, Pakistan, Argentina, Venezuela, and parts of the Arab world. If your business plans rely heavily on these jurisdictions, you may need to consider non-PCT options for filing.

The other form of non-provisional patent application is the utility patent application and, in some jurisdictions, the utility model. Utility patents typically allow for multiple independent and dependent claims and include a 20-year term from the non-provisional filing date with the possibility of patent term adjustment in some countries, such as the U.S.

The utility patent application can be filed directly in the U.S., potentially claiming priority to an earlier provisional patent application, or can enter the country within the 30-month date of a PCT application designating the U.S. In foreign jurisdictions, utility patent applications can enter off the PCT for PCT member countries or can be filed directly, and in most cases claiming priority within 12 months to a U.S. provisional patent application based on various international treaties. We won’t say much about utility models, but they are typically shorter-term and have lower thresholds for patentability. The U.S. does not have a utility model.

Trademarks

Trademarks are vital to intellectual property protection in the agricultural technology industry because they distinguish one company’s products or services from those of another. In this industry, trademarks can protect and promote innovative agricultural technologies, such as genetically modified crops or precision farming equipment. These trademarks are even more powerful when combined with other forms of IP protection. In addition to protecting a company’s brand and reputation, trademarks can complement patents, copyrights, and trade secrets.

For example, a trademark can protect the name of a new crop variety or farming technology, while a patent can protect the underlying technology or method. It’s often important to engage trademark counsel early in the process to avoid choosing a name that conflicts with existing brands and, potentially, having to change the brand altogether down the road.

Trade Secrets

Trade secrets can be a valuable tool for protecting proprietary information in the agricultural technology industry, particularly regarding the internal methods, procedures, and techniques used to produce plant propagation. While trade secret protection is rarely used with plants or plant varieties due to their ability to propagate, the specific techniques and processes used to produce them can be kept confidential and protected as a trade secret. This can include everything from selecting and breeding plant varieties to producing and processing crops.

By safeguarding these valuable parts of their business, agricultural technology companies can maintain a competitive advantage and protect their innovations from being copied by competitors. However, trade secrets require diligent efforts to maintain their confidentiality, and companies must try to prevent their information from being disclosed or misappropriated.

Data Exclusivity

Data exclusivity has traditionally been used to protect trial data in the pharmaceutical industry. But this protection is now being extended to data surrounding the chemicals used in agriculture, such as pesticides, and the testing in which their effectiveness is determined.

According to the European Union, “data exclusivity” refers to the period during which the data of the original marketing authorization holder relating to (pre-) clinical testing is protected. This is an eight-year protection period during which the generic applicant may not refer to the information of the original marketing authorization holder, and “marketing exclusivity” refers to the ten-year period after which generic products can be placed on the market.

Plant Patents

A plant patent allows for a 20-year term to protect a claim statutorily drawn to the plant. This special patent exists in the U.S. and evolved over time. New inventions relating to plants can utilize utility patents to protect intellectual property.

However, under U.S. law, utility patents relating to plants are for claims to genetically engineered or sexually reproduce plants and tubers. Utility patents cannot be used to protect asexually reproduced plants, which are understood to be plant varieties reproduced by means other than from seeds, such as by rooting cuttings, layering, budding, grafting, inarching, etc. In 1930, federal law established a new type of patent (the plant patent), which provided for specific protection of asexually reproduced plants. The Plant Patent Act was based in part on the perception that plants could not be adequately described to meet the description requirements of utility patents.

Although a plant patent has a 20-year term like a utility patent, it has only a single claim directed to the plant, as shown and described in the plant patent application. This patent is unique to the U.S., and there are no international equivalents, so it would not be suitable for an international strategy.

Plant Variety Protection

Plant variety protection, also known as breeders’ rights, is a form of intellectual property protection for new varieties of plants. This protection allows breeders to control the use and propagation of their new varieties for a set period, typically 20 to 25 years, and to receive royalties from their sale. One of the key international agreements governing plant variety protection is the International Union for the Protection of New Varieties of Plants (UPOV), which provides a standardized framework for protecting breeders’ rights worldwide.

These rights are encoded in the Plant Variety Protection Act (PVPA) administered by the U.S. Department of Agriculture in the United States. This law allows breeders to protect sexually reproduced or tuber propagated plants that are new, distinct, uniform, and stable. In addition to granting exclusive rights to produce, market, and sell the new variety, the PVPA prohibits others from using, selling, or reproducing the variety without permission.

Similar laws exist in other countries, such as the Plant Breeders’ Rights Act in Canada, the Plant Variety Protection and Seed Act in Australia, and the Community Plant Variety Office in the European Union, which provides a single system of protection for all EU member states. Plant variety protection is critical to many U.S. and foreign IP strategies in the agricultural sector.

Developing Your IP Strategy

No matter the area of the AgTech space your technology falls into, the timing is right to be developing new innovations in agricultural technology. How you protect those innovations will depend on the nature of the innovation and your business model. In future posts, we will consider specific aspects of intellectual property protection strategies for this growing sector.

Choosing the right intellectual property protection strategy can be a complex process, especially given the variety of options available. Whether it’s patents, trademarks, trade secrets, or plant variety protection, selecting the right strategy can make all the difference in the success of your AgTech business. Contact us today to learn more about how we can help you protect and maximize the value of your AgTech innovations.